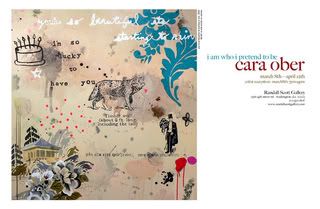

“Painting as a mode of thinking” is the way Holland Cotter described the landscapes of Poussin in a recent New York Times review. He likened Poussin’s artistic practice to a certain kind of poetry in which “antique references, modern speculation and sensual delirium” check and fuel the import of each component. A viewer might do well to keep this conflicted discursiveness in mind when looking at the paintings of Cara Ober. Her art can look deceptively inviting, almost reassuring in its Hallmark Hall greeting card sort of way, as if the meaning of her jumbled references to old-time dictionary illustrations, sentimental silhouettes, wallpaper patterns and middle class sense and sensibility were simply meant to give us pleasure, the concatenation of images and words an apotheosis of middlebrow taste somewhat like the effusions of Jeff Koons, another notable graduate of the Maryland Institute College of Art. But you would be mistaken to think so. Perhaps like Ober you too are a product of suburban America, perhaps like her you too feel conflicted about the comfortable sources of your pleasures, how often they are rooted in a familiar environment, the taste of chocolate cake, a submissive pet, a doting mother, a non-threatening mate. Perhaps her older work made it easy for you to feel some such generational kinship but the new paintings are darker in color, more subtly threatening in their selection of quotes and definitions, more aggressive in their critique. They will remind you that you are not like Cara Ober.

The new paintings require a type of “slow looking”, the eye moving from image to image, the brain attempting to puzzle out Ober’s meanings. The layering of images in modern art has a storied history and a distinguished if controversial line of practitioners including Francis Picabia, Robert Rauschenberg (a hero of Ober’s), Sigmar Polke and David Salle, an artist guaranteed to raise the hackles of anyone with feminist sensibilities. In the layered work of these artists, disjunctive visual signs are used as grammatical equivalents of words in a sentence; Ober’s more lyrical paintings are part of this tradition, visual equivalents to the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E school of poetry in which sound takes precedence over sense, and placement is privileged before meaning. In Picabia the images are literally placed one on top of the other and the layering often achieved through the foregrounding of pentimenti, evidence of previous attempts at achieving visual coherence. This is not Ober’s way, her method closer to that of Rauschenberg and Salle in which the images are dispersed across an abstract expressionist field or ground in the manner of a visual puzzle. Whether these puzzles are actually capable of solution is another matter. Rauschenberg even called one of his most famous combine paintings “Rebus”, the term used for a kind of visual puzzle endemic to game shows but neither his work nor Salle’s is susceptible to a single interpretation, and neither is the work of Ober. You have been warned. On the other hand, there are philosophical and sociological points being made, some of which clearly relate to how art is produced and received; this strategy aligns her with Polke, a contemporary master devoted to the alchemical nature of process, the deconstruction of printing and typography, the flexible meaning of emotionally fraught images both old and new.

With their lipstick colors and feminine cursive, the pre-Pop prints and drawings of Andy Warhol may be Ober’s closest visual ancestor of all; see especially the hand-colored lithographs in A la Recherche du Shoe Perdu (1955) and his series of watercolor cats and butterflies. Like Warhol, Ober calibrates the visual balance between word and image; unlike his cool effusions, she adjusts the emotional heat of her work up or down by introducing stenciled dictionary definitions in the manner of Kosuth and fragments of provocative poetry. And Ober gives her words and images equal visual weight. For this reason alone her work is subliminally hot, unlike the dead pan dictionary photostats of Joseph Kosuth or the gunpowder drawings of Ed Ruscha. In their work words serve as image and conceptual trigger, taking over the entire surface and meaning of the painting or its photographic equivalent. Whether taking her words from her own journal or from poet-friends, Cara Ober is deeply invested in the emotional power of language. Many visual artists are instinctively drawn to poets and their work by the image-making properties common to both art forms: on the one hand, the representation of objects through mark making, on the other, the evocation of images by metaphoric means. The use of words as components in visual compositions begins with Cubism and its invention of collage as an artistic strategy, a means by which the art work became an object in the real world through the reciprocal insertion of fragments from that world, a headline from a newspaper, a musical staff, a torn sheet of faux bois wallpaper; at this critical juncture, Picasso and Braque were surrounded by many friends and associates who were writers and poets: Apollinaire, Max Jakob, Cocteau, and Gertrude Stein. Years later a literary movement actually spawned an entire visual style. Paintings and poems have been twisting around one another ever since, like two strands of DNA. Ober’s paintings are a recent elaboration of this tendency.

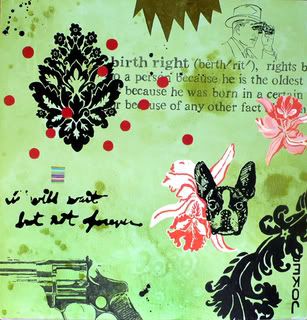

As already mentioned, Ober often employs a delicate “wet” looking scrawl that resembles the blotted line in the early autographic (pre-POP) drawings of Andy Warhol, an artist similarly conflicted about his upbringing; both artists use this technique to draw domestic cats and innocent butterflies, things we are sometimes ashamed to love openly because they are often despised by intellectuals or by the more rational and self-impressed half of our own consciousness. In a painting like “born for better things”, you can still see his influence, especially in the pistols and revolvers so exquisitely hand-drawn that they look like Warholian screenprints; similarly her Pop-inflected 1950s floral patterns look like collage but are not. In this painting, the darker import of the images is reinforced by the aggressively frontal portrait of a dog’s head as well as the scripted message “I will wait but not forever” and the stenciled dictionary definition of “birthright”. The recurring images of Joker playing cards are an almost too-pointed reminder of the game being played on us, the superficially cloying sentimentality and kitsch aesthetic giving way to serious business, the power of the artist to fool the eye and control our emotional weather. How Ober feels about her self-identification with the Joker, the classic camp villain of the Batman comics, is uncertain; we cannot know what she knows, even about herself. Another warning of serious intent is Ober’s employment of opaque figures painted in black that resemble nothing so much as Kara Walker’s sociologically charged silhouettes, themselves as much about femininity as they are about race. You can see this in the lower right-hand corner of “lowdown”, one of the best paintings, fierce despite its use of the older palette as a ground. In the revealingly titled “i regret saying these things too softly”, the dancing couple in the lower right serves a similar purpose and is counterbalanced by the ominous cascade of black paint in the upper left. The instability of truth, whether visual or sociological, is heralded by the choice of her other images, the Joker from an old playing card, the image of a mockingbird, the dictionary definition of a duck decoy. Ober’s pictorial universe is simultaneously campy and obnoxious, sentimental and strident, decorative and awkward, mute and sounding off.

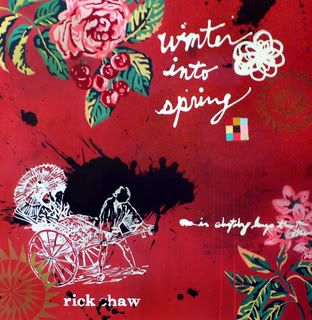

I have already mentioned the scrawled line that Ober uses for quotes from Bob Dylan, from her own journal entries, from pop songs and greeting card verse. Not only are these mostly sentimental messages forced to abut her images but they also must deal with stenciled texts, seemingly banal definitions that she appropriates from her collection of old dictionaries. In “lowdown” the text is taken from Dylan’s “Idiot Wind”, “passing stranger/ someone’s got it in for me/ I can’t help it if I’m lucky”, the quote menacingly divided, the boxer’s head facing the first part. Above the scrawl, Ober has juxtaposed the definition of “lowdown”, a slang term for truth. Over the past few years, her choice of text has darkened along with the color of her figurative and literal ground, almost always implying a feminine critique of masculine appurtenances, male dogs, weapons and tools: since these are the words most frequently illustrated in the old dictionaries, Ober gives us the accompanying drawings, fashioned to look like early lithographs and places them next to the text. In the beautiful “winter into spring”, the hopefulness of the scrawl and the sentimental definition and image of a rickshaw are cancelled by the blot of thrown paint. Across the scumbled abstract expressionist ground of her work, the skin and stain of her acrylic, Ober repeatedly confronts comfort and discomfort, acceptance and criticism, feminine and masculine. In “well-meaning”, the romantic scrawl (“because you are mine”) is negated by the old-fashioned woman with a pompadour hair-do and the male astronaut facing away from her.

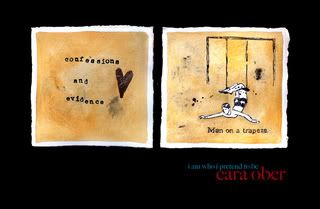

And then there is the wall. Ober has assembled about 150 sheets of six by six-inch paper, each covered with watercolor, gouache, gold leaf and the occasional element of true collage. If her individual canvases seem at first glance like lyrical songs, decorative assemblages of non-threatening images, are her wall-sized concatenations of multiple sheets more akin to symphonies? In taking up this strategy Ober has relatively few precedents, Jennifer Bartlett, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Jim Hodges, Joseph Grigely, and Zak Smith come to mind. Bartlett is the most apposite because she is female and her images are similarly non-threatening and superficially neutral; like Gonzalez-Torres, Bartlett’s paint drop plates and the orchestration of images in “Rhapsody” come out of a post-Minimalist aesthetic. When Gonzalez-Torres traces his lymphocyte counts on graphs he uses the emotionally neutral or cool armature of the grid; without some background information or knowledge of a title we can only guess at the emotionally loaded nature of his project. Hodges fabricates walls of painted flowers that are more object-oriented than the work of Ober. Grigely’s casual notes, meal receipts and phone messages, his “inscribed conversations”, are mementos of his daily exchanges as a non-hearing person negotiating the hearing world. Zak Smith’s most famous wall is even more explicitly language-based even though no words appear; it consists of more than 700 drawings and photo-paintings inspired by every page in his copy of Gravity’s Rainbow (2006). Like Hodges and Smith, Ober’s sheets are physically delicate, seemingly humble and frankly autographic. Like her individual paintings, the “mural” is more than a puzzle meant to be solved, it’s a metaphor for the random connections of daily thought. Because half the piece consists of dictionary images she calls “evidence”, and the other half is primarily text Ober terms “confessions”, we once again sense that familiar unease that Ober injects beneath the surface of her outwardly well-behaved pictures. Unlike a painting, in which the confrontation of text and image must be balanced for color and scale, everything on this wall is given equal weight. Read left to right from a distance, the wall becomes a collection of thoughts and sensations more random than any a painting might achieve; up close we are subsumed in the welter of its jumping off points. If not for the division between image and text the eye wouldn’t know where to turn first. It’s difficult to predict what the recent emergence of wall-sized work presages for her artistic program but it surely is not an attempt to make things easier for the viewer. I strongly suspect she is done with the regret of saying things too softly. Like I said, you’ve been warned.