March 31: DCist Interview: Cara Ober at

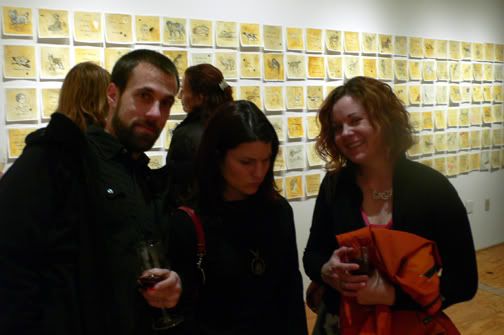

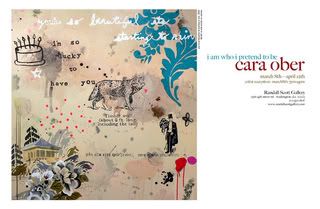

http://dcist.com/2008/03/31/dcist_interview_23.phpCara Ober is a painter, writer and teacher living in Baltimore and showing her work around the region. She teaches at the Maryland Institute College of Art, Towson, Johns Hopkins, and Loyola College. A lifetime area resident, Cara, 33, also writes art reviews for Art US Magazine, Art Papers, and Gutter Magazine. Her latest show, I Am Who I Pretend to Be, runs at Randall Scott Gallery through April 12.

What are some of the ideas and themes that your work engages with?

I am a storyteller, but my paintings have more in common with poetry than traditional narratives or prose. The stories I tell are mostly autobiographical and personal – my “material” is what I know, what I experience, and what I learn on a daily basis. Painting is a mode of thinking for me. It is a way for me to examine the fragments of memories and moments and to combine them in a way that is more interesting and, possibly, more real, than the way they were originally experienced.

The theme of memory in art seems really played out right now – a cliché – and, often times, I think an artist’s memories are so tender and so poignant that they interfere with the editing required for solid visual work. I think a lot of art about this subject – memory, consciousness, the unconscious – is half-assed.

However, I’m at a point where I know what I am interested in and there’s no getting around it. I can’t invent a concept and manufacture excitement about it. In graduate school, I attempted to be more “conceptual” in my studio practice and it always felt artificial and flat. I am interested in exploring the mystery of the personal self; the interior life lived in the brain, and, specifically, mine.

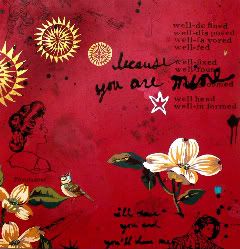

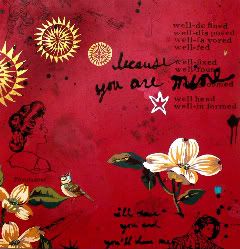

Well Meaning, Cara Ober

38x40"

Painting on canvas

Who are some of your artistic inspirations?

I think Louise Bourgeois is about as great as they get. She makes powerful works, which are simultaneously personal and universal, still and she’s in her nineties... About two years ago, the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore showcased Bourgeois’s works, in which over half were made in the last decade, but integrated it throughout the museum. So there would be a six hundred year old suit of armor next to a Bourgeois felt figure, an ancient Sumerian necklace next to a Bourgeois necklace… not only was it interesting to have to hunt for the contemporary work among the antiquities, but her work, so steeped in these dark and mysterious taboos, made me see this universal relationship between time periods, styles, and people. I’m not really interested in historical works of art – I prefer contemporary work – but Louise Bourgeois’s work in that context made me see the Walters’ collection in a new light.

How long does it take to make a typical piece?

The timing depends on whether the piece is cooperating or not. I’ve made terrific paintings in a week’s time... Working fast and furious is the best way for me to do two things: to make unselfconscious decisions and marks, and to inject a sense of urgency and passion into the work. The surprises that come from hasty painting are the spark that keeps them alive. I’ve also struggled for months and months on one painting, only to paint over it yet again. I typically paint over old paintings – I like to see the history of past decisions buried under the surface of the paint.

What materials do you work with?

I use acrylic and oil paint, both for different reasons. I use acrylic because I am impatient and like to work fast. I can rapidly build up a surface and then change my mind a lot – paint things in, take them out, paint over them, put them back in again – lots of back and forth. But I like to use oil for the top layer because the color is richer and more unpredictable, especially when thinned down into stains or pours.

Your new show at Randall Scott is entitled I Am Who I Pretend to Be. Is this a reference to the recent controversy with Christine Bailey?

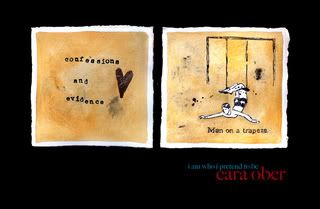

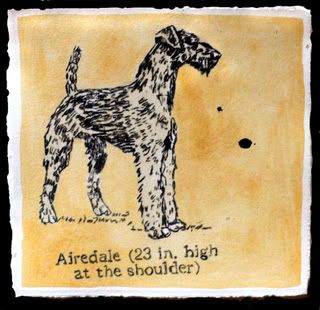

Yes and no. I started working on a series of small drawings, all about six by six inches, last November for the show at Randall Scott. I think I was feeling stumped and wanted to dissect the process of painting a bit, taking it apart piece by piece, make it more fun and less intimidating. So, I started out with all of these images from the dictionary, lots of dog breeds and musical instruments, just silly images, one on each piece of paper, and then I felt that the growing stack of drawings needed another half. I thought about what they all had in common and decided all are presented to the world as factual evidence. And we all know that facts are just part of the story. The other half is the opinions and intuitions lurking beneath the surface, most of which are not appropriate to share with others.

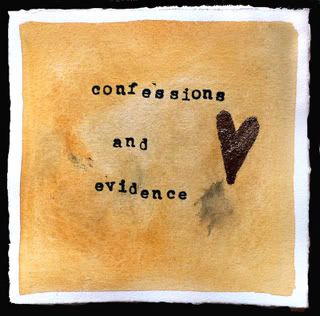

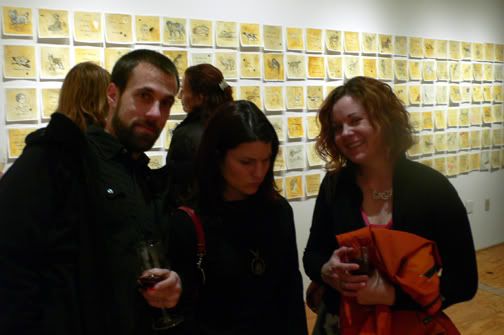

So I started working on another series of small drawings, to enhance the first series, just writing phrases you’re not supposed to say in public, and these became the "confessions," which complete the story. (The installation is called Confessions and Evidence, above, and is 160 drawings in all). One of the confessions I wrote at that time was “I am who I pretend to be.” I didn’t really think about it much… I mean, I write little phrases down all the time, especially when I am driving, and it made sense on a lot of levels. I think I was really thinking about that particular phrase in an inspirational way, like, you can be who you want to be – you can do it!

But later, after the "Bailey incident," as we call it here in Baltimore, I came across the statement and its meaning was completely different and not at all what I had intended. It just smacked me in the gut, this small drawing. Here was this person pretending to be me, in her work, and here I am, just trying to be myself, through the same exact process. It was bizarre. Like most of my decisions in the studio, that drawing was a happy accident and I didn’t even realize until long after I had made it. When I rediscovered that drawing, it felt like the theme of my work was staring me in the face and I have another artist to thank for it, I guess.

Do you have a favorite art spot or event in D.C. or Baltimore?

Yes. It is my studio! It is in my basement these days, after the condominium culture ate up my warehouse space. I try not to go out too much, although I do go to my share of art shows, especially in order to blog about stuff. I love going galleries that are professional without being snooty. I think the Randall Scott Gallery definitely fits this bill, and so does Gallery Imperato who reps me in Baltimore, as does Paperwork in Baltimore, which is a space I’ve opened up recently with my friend Dana Reifler.

How would you describe the art scene or community in D.C. or Baltimore?

As an artist who’s been showing both in D.C. and Baltimore for a couple of years, I have to say the two are completely different. I like making art in Baltimore, because I can afford to have a lot of studio space and freedom to experiment. Baltimore’s art community is supportive and warm, and is definitely thriving, but there isn’t much economic backing for it, other than grants. I sell a lot less work in Baltimore than in D.C., although the press in Baltimore is more encouraging, with lots of opportunities for reviews and write-ups.

In general, D.C. is a cooler, more intellectual city, and also more wealthy. I discovered blogging, after my first show in D.C. There were no art blogs in Baltimore a couple of years ago. There are many more professional galleries in D.C., which tend to exhibit commercial work and also a few more museums that collect contemporary work. This work isn’t always as dynamic or vital as the work I see produced in Baltimore, but it is definitely exhibited more professionally.

I think I am really lucky to be able to be a part of both the Baltimore and the Washington art community. I think I learn a lot, professionally, from both spots, although I get a lot more speeding tickets in Washington.

What do you see down the road artistically?

I like to be busy making things at all times. My goal would be to have projects aplenty, some solo and some collaborative, for the rest of my life. I would like to teach less and paint more. I would like to continue to curate exhibits with interesting people and in challenging places. I would like to get paid to write about art. I would like to travel to lots of new places to make, curate, and write about art. I would like to be awarded some grant money so I can do nothing but make paintings for a while and not leave the studio and really get to know myself. And eventually, I would like to be a really busy old lady, as ready for the next painting, and the next show as I am now.

To hear more from Ober, the Randall Scott Gallery will be holding an informal chat with her on April 5 from 4:30-6 p.m. Brandon Fortune, curator of painting at the National Gallery and Kriston Capps, critic for the Washington City Paper and blogger will conduct an informal interview with Ober about her work.

By Amy Cavanaugh in Arts and Events